Vipassana, etc. – part 1

Recently I attended a 10-day vipassana meditation retreat, specifically one in the tradition of S. N. Goenka. Here are my observations.

I. Meditation is a good way to find out how often you get distracted

The first thing that becomes apparent during meditation is that a large chunk of your thoughts is completely useless and prevents you from spending time productively. We’ll go deeper into “completely useless” in later sections. For now, let me describe how to replicate this result if you want a show-not-tell.

Sit on the floor. Ensure there are no distracting lights, sounds, smells. Keep your spine and neck straight; don’t lean against anything. Make yourself comfortable, perhaps with the help of several pillows. Close your eyes. Observe your breath.

Ideally, do this for ten hours every day – but even two hours could be enough, I’m not sure. If you’re meditating on your own, consider warning people around you – especially if you’re stubborn and would rather die than meditate for [less than ten hours] when somebody tells you that you can do [ten hours].

- Day 1: observe your natural breath. Pay attention to every inhalation and exhalation. If your mind wanders away, don’t judge yourself – think “my mind has wandered away” and return to observing the breath. Try also doing it during your “normal” life, outside of the meditation hours.

- Day 2: now that you can stay focused on the breath – start observing how the air touches your upper lip, how the temperature of your nostrils changes when you inhale/exhale, how sometimes your upper lip can feel tingly or sweaty or pulsating, etc. Just whatever happens to your upper lip and nostrils, observe it.

- Day 3: same, but slightly harder – the insides of the nostrils are excluded from observation.

Why breath? First of all, it’s always with you and so you can practice at all times. Second, it’s one of the few things that happens naturally and can also be controlled (if you find it hard to focus on the natural breath). Third, it is connected to your emotional state and so you can notice how your emotions affect you physically – which will be useful later.

For me, the result was that sometimes I would lose track of my breath every 5–10 seconds. Not great.

II. You get distracted mostly at “I want X” and “I don’t want Y”

Let’s look at distracting thoughts more closely. Goenka categorizes distracting thoughts into “cravings” and “aversions” categories (happy/unhappy), and further notes that they are mostly about the past or the future; this matches my experience.

- Happy thoughts: I am getting back to specific moments in my past, or thinking about something that will happen in the future, over and over – merely to feel good. Even worse – when I ask myself “would I fast-forward my life to the moment when X finally happens?”, the answer is often “I shouldn’t but I kinda want to”.

- Unhappy thoughts: “I don’t know what I should have done in situation X”, or perhaps “I know what I should do in situation X but don’t want to accept it, is there any other way?”. This goes back to Peterson and “if you’re still feeling upset about something that happened more than 18 months ago, you have a problem”. See also: a key metric of mental health is how many of your thoughts are new thoughts vs old thoughts.

In theory, the categorization above is incomplete. There could be more kinds of thoughts: productive analysis of something that happened in the past, productive planning of something that could be done in the future, or general observations like “my life sucks/is awesome” or “hey, what is happening is kinda interesting”. However, in practice those occur rarely compared to {craving, aversion} {to past, to future} kind of thoughts.

III. An interlude: show-not-tell is great

The reason I’m not spending much time describing cravings and aversions is that they are much easier to grasp if you have actually observed them flashing through your mind in real time. It also makes it much easier to believe that they are the predominant concern of your mind, as opposed to “eh, maybe 20% or so”.

Vipassana is quite explicit about this. Specifically, they identify three kinds of knowledge (or “wisdom”, in Buddhist terminology):

- Received knowledge: somebody told you that X is true.

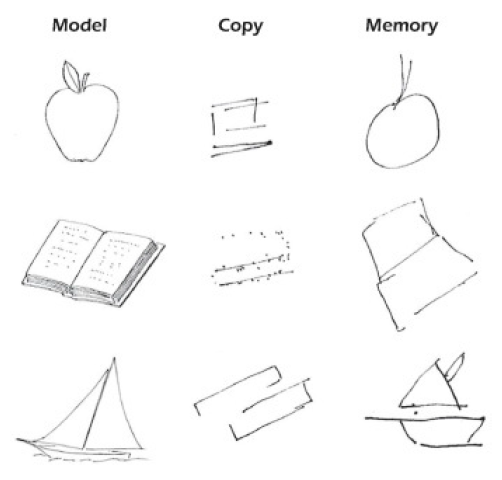

- Intellectual-level knowledge: you have decided (hopefully by some rational process) that X is true.

- Experiential knowledge: you have observed that X is true.

Then they flat-out tell you that experiential knowledge is the best and the other two are somewhat useless. This, by the way, sounds like a great thing to keep in your mind whenever you are teaching somebody – if they are not getting experiential knowledge, look for a way to change that.

Thanks to the controlled environment, vipassana instructors are able to demonstrate: “Look, you’ve been given a really simple task. Observe your breath. And hey, you’re failing it! Such a simple task, but you’re failing it. This is because your mind wanders a lot. And look where it wanders – craving and aversion. Mostly just craving and aversion.” Then you can look at your life prior to the retreat, remember all the tasks that you have failed because of your wandering mind, and categorize the distractions into cravings and aversions. Intellectual-level knowledge becomes experiential knowledge post hoc.

As a side note, this is also why “giving names to things” is a useful practice in general. By recognizing something as a Thing That Happens, it becomes easier to remember when it happened previously, and notice it when it happens in the future. You can’t collect experiential knowledge on X if you don’t make sure to put all X-related things in the same bucket – and the way you construct this bucket is by giving X a name.

IV. I’m claiming that happy and unhappy thoughts are useless

My indictment against both happy and unhappy thoughts is that a) they are useless and b) they prevent me from mastering whatever I am doing right now.

With unhappy thoughts, you could make a case that being unhappy about something can help you avoid it; I have nothing to say about this except for “yeah, you would think so”. In reality, being afraid of X mostly just makes me avoid any thoughts about X, including “how can I solve X”, so it doesn’t help. There’s no reason why this must be the case, but empirically, this is what happens.

The case for happy thoughts is more interesting. You could object:

Happy thoughts make you feel good and this is an Intrinsically Valuable Thing. Don’t you want to feel good?

Counterobjection: there’s a difference between happiness (emotional well-being) and satisfaction (evaluation of life). Happiness is feeling good right now, satisfaction is looking back at your life and thinking “okay, this was good”. Can I prove that you should strive for a satisfying life as opposed to moment-to-moment happiness (or even the feeling of satisfaction)? No, if only because bridging the is-ought gap is a fool’s errand.

Again, this is as far from a well-developed argument as you can possibly get, so treat it as a statement along the lines of “I’m going to believe this until I find something better”:

- Worrying doesn’t let you avoid danger.

- Happiness doesn’t make you more satisfied.

- So don’t worry and don’t be happy. Think something useful instead and you’ll get better at avoiding danger and at being satisfied.

V. “Can you clarify this thing about happiness vs. satisfaction?”

One of the best introductions to “happiness vs. satisfaction” is long-winded, rambly The Tower. You will like it if you like The Last Psychiatrist and sam[]zdat. Here goes an extensive quote.

The question is thus: why don’t we choose to be happy?

For those who doubt humanity’s anti-joy stance, look no further than the sci-fi concept of Wireheading. If in the year 20XX the Hegemony announces a Guaranteed Happiness Machine, would you use it? There’s no catch. [...] The feeling it gives you isn’t mere hedonistic pleasure, it is limitless understanding, loving and being loved, progress and growth—whichever nouns or adjectives you prefer, the sum feeling is happiness. [...]

I have no doubt that some readers would hit the ON button so hard they’d break a metacarpal. Not unreasonable, if you are depressed or a hippie circa 1967. I can’t question your axioms, I’ll drop a few nickels when I pass by on Telegraph Ave. Those of you who reject suicide by Hallmark, I agree, but please note that instead of happiness, equanimity, transcendence, or any other internal state postulated as the ‘meaning of life,’ you are prioritizing something that is not a feeling at all.

A second thought experiment re: that something. Suppose that your behoodied Silicon Valley boss offers you an all-expenses-paid vacation to virtual reality paradise. [...] Alas, for copyright reasons, any memories of the vacation will be wiped upon your return, any skills you acquired will be unlearned, and any metadata of your adventures will be destroyed. [...] I’m more tempted by dreamland than the empty calories of wireheading, but even so I recognize that both choices are fundamentally the same: an ecstasy that leaves no trace vs. bland but tangible reality. The decision is almost binary. If you would spend a year in the Matrix, why not twenty? Why not the rest of your life?

These concerns are not theoretical.

In the study, Kahneman and colleagues looked at the pain participants felt by asking them to put their hands in ice-cold water twice (one trial for each hand). In one trial, the water was at 14C (59F) for 60 seconds. In the other trial the water was 14C for 60 seconds, but then rose slightly and gradually to about 15C by the end of an additional 30-second period.

Both trials were equally painful for the first sixty seconds, as indicated by a dial participants had to adjust to show how they were feeling. On average, participants’ discomfort started out at the low end of the pain scale and steadily increased. When people experienced an additional thirty seconds of slightly less cold water, discomfort ratings tended to level off or drop.

Next, the experimenters asked participants which kind of trial they would choose to repeat if they had to. You’ve guessed the answer: nearly 70% of participants chose to repeat the 90-second trial, even though it involved 30 extra seconds of pain. Participants also said that the longer trial was less painful overall, less cold, and easier to cope with. Some even reported that it took less time. (Summary by this website, source Thinking Fast and Slow)

Ur-Rationalist Daniel Kahneman distinguishes between the experiencing self, which reacts to the bartender’s “you’ve had enough” with pain fiber shocks of disbelief, and the remembering self, which, subject to biases such as duration neglect and the peak-end rule, leaves the two star Yelp review. The cold water experiment is a brilliant demonstration of how, as in the wirehead and dreamland examples above, our remembering and experiencing selves often disagree. This should be intuitive: consider the TV series ruined by the finale, the regret that follows junk food bliss, or the bad date that turns into a comedic memory.

Except Kahneman doesn’t take his idea far enough. Consider the motivations of a suicide bomber. The experiencing self knows nothing save immediate pleasure and pain. It has no interest in martyrdom. It will only pull the trigger to end some greater agony, such as during sickness, when some elemental part of you literally does “want to die.” The remembering self is what chooses to endure the flu, since it knows from its internalized stories that all pain eventually subsides; failure of this mechanism is the cognitive basis for depression. At times, the remembering self will even coax the experiencing self into discomfort, e. g. work, in exchange for a future reward, e. g. dough. But the case of a kamikaze, the remembering self is willing to die not for its own postponed pleasure, but so that some other remembering self can look back on its behalf.

VI. Goenka goes further and claims that desires are harmful

Vipassana approaches the topic from a different angle: thoughts are not just “happy” and “unhappy”, but cravings and aversions. They lead to suffering either directly or indirectly. Thus, they must be eliminated.

If you crave something you cannot get, you are miserable; if you cling to something you already have, you will be miserable when you eventually lose it. If you get attached to your beliefs, you will be miserable when you come in contact with people who have opposing beliefs; and since some of your beliefs are necessarily false, you will suffer when they get shattered by reality.

This immediately poses a problem: if you don’t experience craving or aversion towards anything, how can you decide how to act? The answer is that empirically, action (and “will” in general) does not require craving or aversion. You don’t have to be afraid of fire to know that you shouldn’t put your hand in it. Or, speaking more generally: the mechanism of goal attainment does not have to be implemented via punishment and reward.

This is a very fun road, and it can lead you to interesting places. For instance, if you had a general habit of viewing people as optimization machines, maximizing some utility function that gets more and more convoluted with every thought experiment thrown at you, consider a blue-minimizing robot. There are things for which the best model is not “optimizing”, but “executing a behavior”. What if you are like this, too?

Goenka implies that you can kill certain emotions – judgment, craving, aversion – and still function either the same way, or even better than you functioned before. He does not make a terribly convincing case for it, but it seems plausible. (He also argues that killing those emotions is the first step towards achieve nirvana, i.e. a liberation from repeated rebirth. I will skip this part.)

VII. If you don’t think you can get by without desires, wait till I claim that you can get by without free will

“Desires are optional” is not where the road ends. Read Weird experiences: free will mishaps, where I argue that the whole concept of free will is rather dubious and that you do not even need an internal monologue to function.

To be continued

Getting rid of craving and aversion seems to be the first step towards enlightenment. In the next post I will talk a bit about why I don’t want enlightenment – there are more reasons than merely not wanting to become a philosophical zombie – and then switch to unrelated matters.